Redlining and Housing Discrimination

Understanding Redlining

In the intricate fabric of America’s economic history, one dark thread stands out starkly: redlining. Our exploration into this insidious practice reveals a deeply rooted form of systemic discrimination that has left lasting scars on communities, particularly those of racial and ethnic minorities.

At its essence, redlining is a discriminatory practice where banks and institutions withhold various financial services, especially mortgages, or offer worse rates to residents in specific neighborhoods based on their racial or ethnic composition. Despite its formal outlawing in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act, redlining’s repercussions continue to reverberate through various forms of discrimination today.

Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma – which is living with the results of other people’s

John Mehediis

Historical Roots of Housing Discrimination

Our journey into the history of housing discrimination unveils a persistent pattern. Even fifty years after the abolition of slavery, local governments maintained housing segregation through exclusionary zoning laws. The Supreme Court’s ruling in 1917 against these laws prompted homeowners to swiftly replace them with racially restrictive covenants, denying certain racial groups the right to buy property.

Federal Complicity and the Birth of Redlining

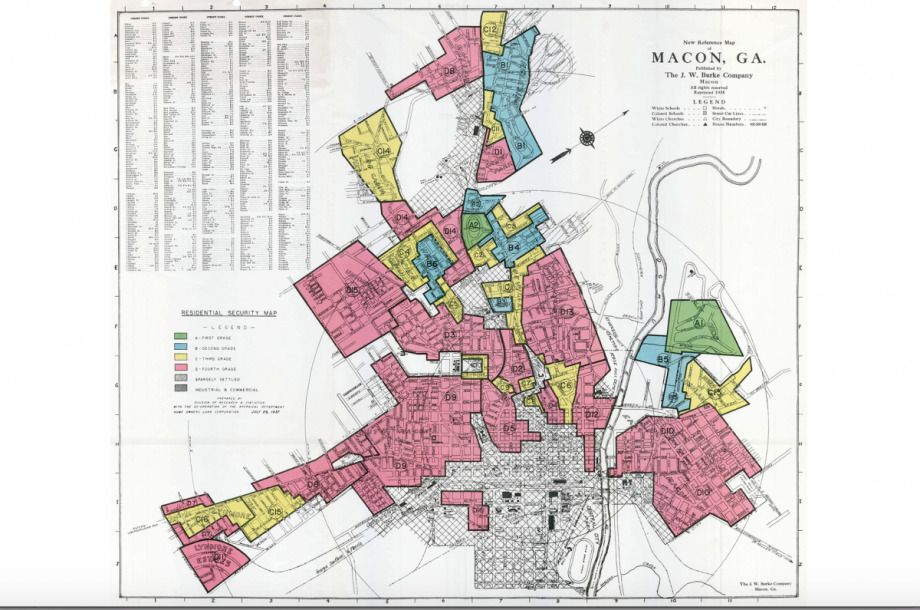

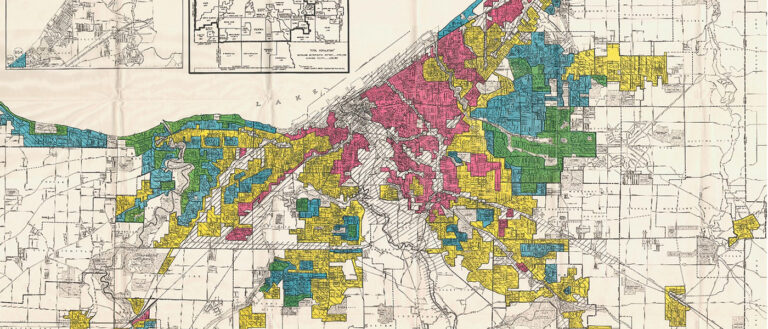

The 1934 creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) marked the federal government’s entry into housing affairs and government sponsored segregation. Instead of fostering equity, the FHA took advantage of racially restrictive covenants, insisting on their use in insured properties. Collaborating with the Home Owner’s Loan Coalition (HOLC), the FHA introduced redlining policies in over 200 American cities.

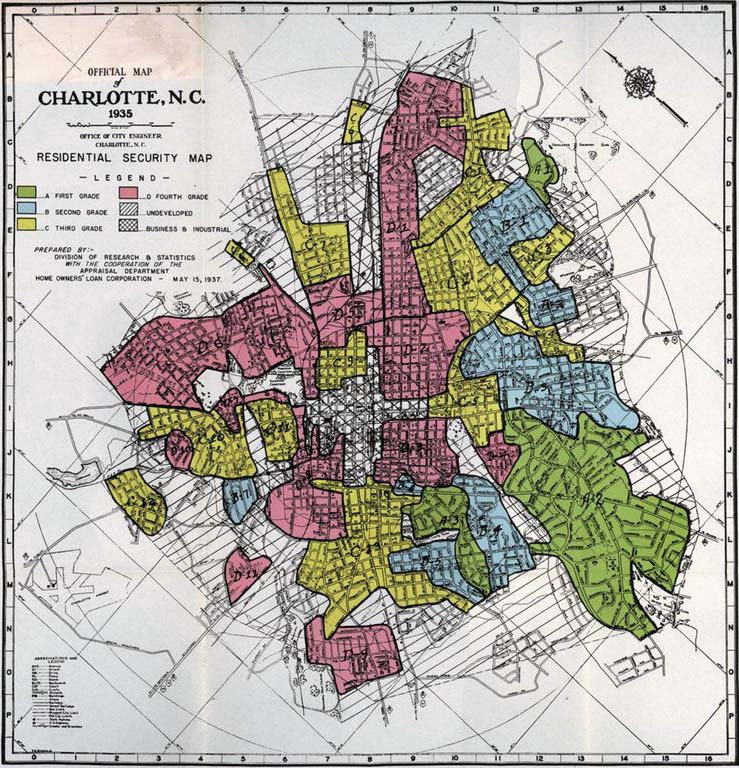

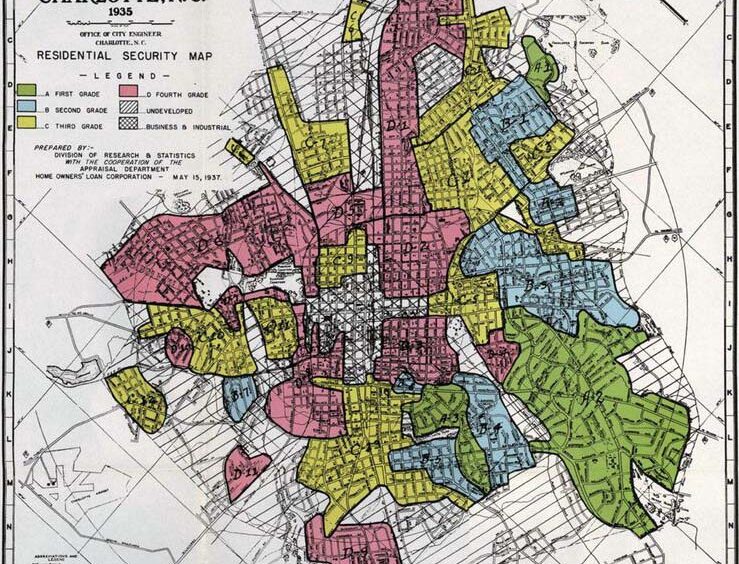

The Color-Coded Discrimination

The HOLC’s “residential security maps” became instruments of discrimination, color-coding neighborhoods to guide government investment decisions. Green areas were considered the “best,” representing in-demand, predominantly White neighborhoods. Blue areas were “still desirable,” yellow ones were “definitely declining,” often bordering Black neighborhoods, and red areas were “hazardous,” ineligible for FHA backing, mostly inhabited by Black residents.

Impact and Lingering Effects

The formal end of redlining with the Fair Housing Act did not eradicate its impact. A 2008 study highlighted disproportionate loan denial rates for Black individuals in Mississippi, while investigations into financial institutions like Wells Fargo in 2010 revealed continued discriminatory lending practices.

Beyond Mortgages: Widening Impact

Redlining’s effects extend beyond mortgages. Supermarkets in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods have been found to raise prices on certain products. The impact is enduring; neighborhoods marked “Yellow” or “Red” in the 1930s continue to grapple with underdevelopment, vacant buildings, and limited services.

Continued Struggle for Recovery

While redlining policies were officially ended, the recovery process for affected neighborhoods remains insufficient. Blocks in these areas continue to face challenges with underdevelopment, a lack of basic services, job opportunities, and transportation options.

A Call for Equity

Redlining stands as a testament to the deeply embedded systemic discrimination in America’s past. It is not just a historical artifact but a living legacy that requires ongoing efforts to rectify past injustices and build a more inclusive and equitable future for all. As we unveil the layers of redlining’s impact, we are confronted with a call to action—a call for a society where every individual, regardless of their racial or ethnic background, has equal access to opportunities and resources.

English

English